Your product lives or dies by a single assumption

A look at the silent bets behind some of the biggest wins and failures in gaming.

Every product decision rests on assumptions about user behavior, psychology, incentives, and the surrounding ecosystem, even if you’re not explicitly aware of them.

Some assumptions validate and unlock massive success. Others fail hard, and nothing that comes after matters. Many products, services, or games we know today wouldn’t have survived if one key assumption behind their design hadn’t been validated.

Let’s deep dive into the gaming ecosystem to uncover some of those assumptions and what we can learn from them.

Clash of Clans

The free-to-progress model

Assumption: Players will tolerate long timers if the core loop is rewarding and social.

You can play Clash of Clans for free, and the monetization never directly breaks fairness. The whole model relies on a small percentage of spenders funding the ecosystem while everyone else is willing to grind. And players accept that grind because the game gives them enough reasons to wait.

Timers aren’t just friction, they are part of the engagement loop. Waiting brings players back multiple times a day, which makes clans more meaningful and turns progress into a shared experience. And because spending only accelerates progress, most players tolerate the grind.

Slow progression almost becomes an advantage. It stretches the lifetime value of players instead of hurting it. The game always gives you a clear next step. There’s always another upgrade, another goal, another thing to push toward. That sense of forward momentum keeps players emotionally invested for months, even years.

Pokémon GO

Real-world movement. For a while.

Assumption: Players will physically move in the real world to play a game.

At first it looked like the assumption worked. But was it really the gameplay loop convincing people to go outside and move? Or was it the hype, AR novelty, and nostalgia?

The problem was simple: the assumption wasn’t backed by a sustainable long term motivation. As novelty decayed and there weren’t enough long term goals to justify the effort required to go out and play, which is a hard requirement, the behavior faded.

Microsoft Mixer

A reverse network effect case study

Assumption: If big names move, their audiences will follow, and then smaller creators will follow them.

Now we know that live streaming doesn’t work like that. Viewers don’t choose platforms only based on creators, their friends and community play a big role too. So when Microsoft bought some big creators, it wasn’t enough for the audience to app-hop from Twitch or YouTube.

Small and mid-sized creators didn’t want to rebuild from zero either. Culture and community turned out to be not just sticky but non-transferable.

Diablo III’s Auction House

The danger of optimizing the wrong value loop

Assumption: Players want a safe, official way to trade valuable loot.

Diablo II had rampant item duping, black market trading, and scammers. Blizzard assumed that if they provided a secure trading system, players would love it.

Instead, they replaced loot hunting with loot shopping. The Real Money Auction House killed the ARPG fantasy: the joy of discovery, unpredictability, and dopamine. Because you could buy a better item in seconds. Players didn’t want efficient trading. They wanted meaningful loot drops.

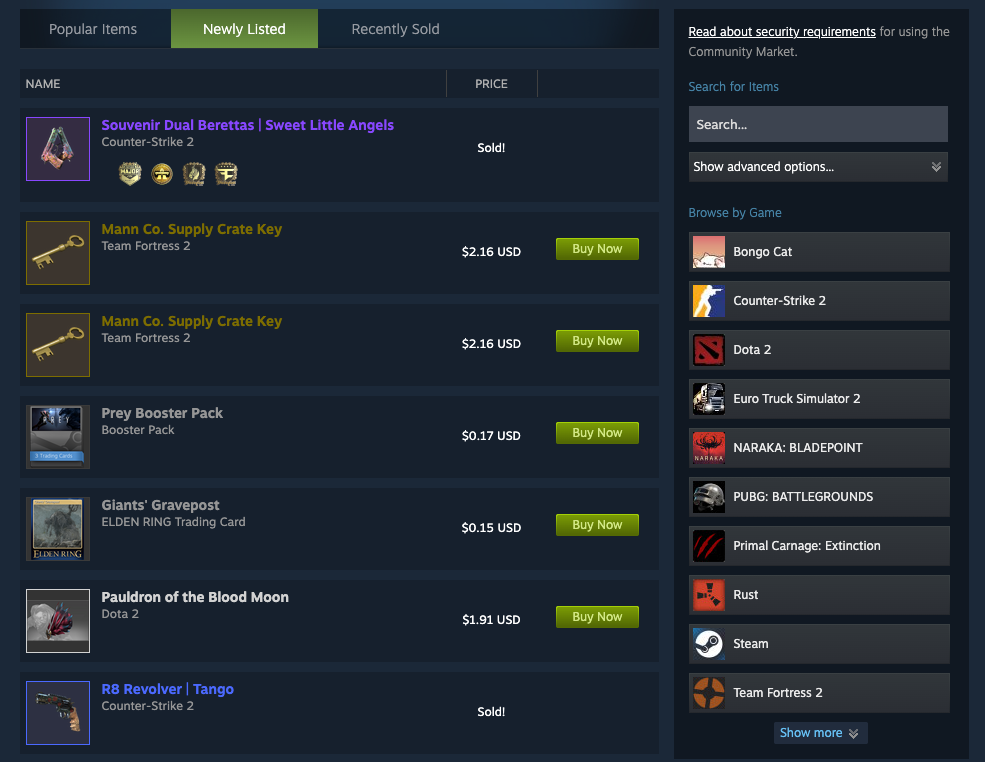

Steam Marketplace

A player driven economy that actually works

Assumption: Players will reliably assign real value to digital cosmetic items and participate in a regulated secondary market.

This is an example where a player driven economy and network effects actually work.

Valve bet on a bold premise: players wouldn’t just collect in-game items but they would trade them, speculate on them, and form a functioning economy around virtual goods. This wasn’t obvious. Most player driven markets collapse due to fraud, inflation, or lack of trust.

But Steam’s Marketplace had two stabilizers:

A creator ecosystem (Steam Workshop) continually introduces fresh supply and novelty.

Money stays inside Steam’s economy, increasing spending instead of draining it.

The result: a liquid, self-sustaining trading economy backed by strong network effects.

In the end, every product runs on assumptions. Just make sure yours aren’t shallow. The real user need is usually hiding underneath the one you think you’re solving. Look deeper, test early, and let the truth surprise you.

This is my favorite post so far. Today we were discussing this exact same subject and I showed examples from the post. Apparently my friend also experienced that Diablo change, he was one of the players who got upset about that change. 😂 And apparently they also revamped some of the prices. Some items lost their value after revamp. Seems like they did series of "bold" assumptions to kill the feature/product itself. 😂